According to a report by Fars News Agency from Zanjan, in a country whose youth thirst for knowledge and whose future hinges on technology and innovation, sometimes a bold move can change the course of events. When formal support wanes, it is faithful hearts and the helping hands of the people that can illuminate the path of science. The “AmirAalam Electronic Materials Laboratory” in Zanjan is not merely a research space, but a manifestation of the will to turn scientific dreams into tangible realities.

Davood Abbaszadeh, the director and founder of this laboratory, a researcher hailing from Khajoo in Maragheh, demonstrated from the outset that science and motivation, when united, can carve paths under any circumstance. He began his higher education at Sharif University of Technology and continued to the highest academic levels in Europe. Upon his return to Iran, he resolved to devote his knowledge to the development of his country. Yet, contrary to expectations, what he encountered was not major government support but closed doors and repeated indifference.

Nevertheless, Abbaszadeh did not give up. He turned to a model widely used in advanced countries for rescuing science—relying on public will and charitable contributions. The fruit of this perseverance and faith is a laboratory that has now become one of the national centres for innovation in electronic materials.

In this interview, Davood Abbaszadeh recounts the challenging journey that began with a simple idea and has now grown into a 120-billion-rial centre pushing the boundaries of science in the field of electronic materials and emerging technologies.

If you wish to know how a laboratory founded on philanthropic support rather than government funding has become a model for advanced, application-oriented research, read the full interview below:

Fars: Please introduce yourself.

I am Dr Davood Abbaszadeh, born in April 1979 in the town of Khajoo, near Maragheh. I completed my MSc in Solid-State Physics at Sharif University of Technology and received a second MSc in Nanoscience from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. I earned my PhD in the Physics of Electronic Materials from the same university and later pursued postdoctoral research at Jönköping University in Sweden. I am currently a faculty member and head of the Electronic Materials Laboratory at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Basic Sciences (IASBS) in Zanjan.

Our mission is to train skilled specialists

Fars: What was the purpose behind establishing the Electronic Materials Laboratory, and what missions is it intended to fulfil?

The main aim of founding this laboratory was to address a serious gap in the field of experimental physics of electronic materials in the country. Unfortunately, despite the fact that technologies based on electronic materials are foundational to many of today’s smart devices and advanced technologies, this field has been largely neglected in Iran. The laboratory seeks to provide the grounds for research and development in semiconductors, advanced materials, and related technologies. Our mission includes training specialised personnel, developing indigenous technologies, and supporting advanced research in this area.

Fars: Why was this laboratory established at the IASBS in particular?

After returning to Iran and completing my studies in experimental condensed matter physics, particularly semiconductors, I received no serious support despite submitting numerous proposals. So I decided to adopt a model that has succeeded globally: mobilising public and philanthropic support to launch a real research centre. The IASBS, with its suitable environment and warm reception of the idea, proved the best setting for this initiative.

Main focus of the laboratory is on semiconductor device research and development

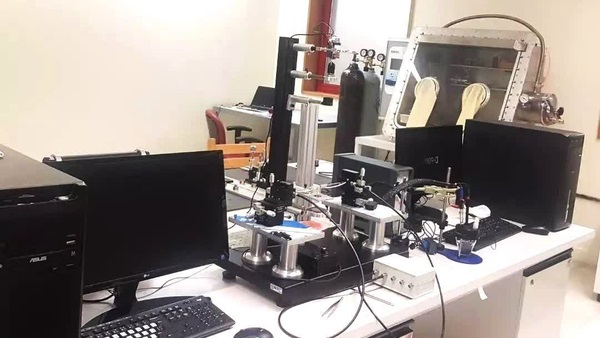

Fars: What exactly does the laboratory do, and what equipment does it house?

The main focus is on the study and fabrication of semiconductor components, advanced materials for electronic devices, and the physical characterisation of materials at the nanoscale. The lab is equipped with advanced tools such as chemical and physical deposition systems, conductivity measurement devices, and instrumentation for device fabrication and testing. Additionally, the laboratory accesses general facilities within the IASBS such as atomic force microscopy (AFM), chemical analysis, and spectroscopy services, which complement the fabrication and testing of electronic materials.

Laboratory offers both education and research opportunities

Fars: What kind of students are eligible to work in this laboratory?

Students of physics, chemistry, electrochemistry, materials engineering, nanotechnology, and even electrical engineering, especially those focusing on electronics and nano, are our main audience. Moreover, postgraduate students in condensed matter or experimental physics can engage in deeper research activities here. Our aim is to provide both educational and research opportunities, and in the near future, to take steps towards commercialising the technologies.

Our goal is to localise cutting-edge science

Fars: What projects is the laboratory currently focused on?

We are working on projects such as energy storage devices, solar-to-electric energy conversion, and the development of novel electronic components like resistive memory devices. These memories operate similarly to the brain’s synapses and are expected to revolutionise artificial intelligence and edge processing.

Our aim is to localise cutting-edge scientific advances. Solar cells, advanced batteries, supercapacitors, and memory devices are all technologies that Iran urgently needs. We are a large country with high energy demands, and if even 50 percent of vehicles become electric, air pollution in Tehran would significantly drop. Moreover, manufacturing state-of-the-art solar panels using our abundant solar energy will create employment and lead to sustainable domestic energy without reliance on foreign countries.

The main obstacle is lack of infrastructure for applied research

Fars: What problems in the field of electronic materials can your laboratory help to address?

The major problem is the lack of infrastructure for applied research and real-world prototyping. Many university projects remain at the paper stage due to lack of facilities. We aim to break this cycle. Our goal is to produce genuine scientific and technological output tailored to industrial and technological needs; from energy generation and storage devices to displays and electronic chips.

70 percent of the funding was provided by the Ghazanfaryan family

Fars: Was the laboratory entirely established through philanthropic support?

Yes, the reality is that the laboratory was primarily founded with charitable contributions. Around 70 percent of the total cost was covered by the esteemed Ghazanfaryan family, and in particular, by Ms Iran Gholami, mother of the late AmirAalam Ghazanfaryan, the first Iranian medallist in the International Olympiad. She was one of our greatest benefactors and never hesitated to help with the development of the lab.

Sometimes we would shyly ask for something, say we needed a particular device, and she would promptly assist, allowing me to go and acquire it.

When the first phase of the lab officially opened and drew significant attention, we realised the existing space was no longer sufficient and that we needed to launch a second phase. This required about 10 billion rials, which again she generously provided without hesitation.

What matters most is that she, whom I refer to as “Lady Iran”, came to truly believe in the value of this path. She voluntarily supported the endeavour with enthusiasm, which was deeply encouraging.

The laboratory is now valued at over 120 billion rials, and I can confidently say that more than 80 percent of this amount has been covered by benefactors. Some people contributed by purchasing specific equipment, worth 1 to 3 billion rials, and others donated smaller amounts, several hundred thousand tomans, which were equally valuable to us. The real value of these donations lies beyond the figures; they helped keep the flame of research burning.

We now need support from the state, institutions, and industry

Fars: Are philanthropists still willing to support the lab?

They help as much as they can, but the economic conditions in the country have affected them too. Even those who once supported us eagerly are now unable to provide the necessary funding. We are at a stage where we need more sensitive equipment, but cannot obtain it through current methods.

That’s why we hope the government, supportive institutions, and industrial firms will step in to assist such projects. The future of the country depends on these efforts.

Of course, to reach the global level, we need access to highly specialised, costly devices. Without them, we cannot attain the desired level of scientific excellence. Serious and targeted support is essential.

Fars: How many people are currently active in the laboratory?

Currently, there are around four MSc and eight PhD students actively working on their respective projects. In addition, other students from physics, chemistry, electronics, and engineering regularly visit the lab for internships or collaborative research.

I am committed to expansion

Fars: Do you have any plans for further development of the lab?

Yes, we are constantly pursuing development. We speak with philanthropists, physicians, well-off professors, and even ordinary citizens. For example, a renowned doctor in the city currently donates monthly, partly to support underprivileged students and partly for the lab’s sustainability. We run awareness campaigns on Instagram and Telegram to educate the public. The goal is to spread the culture of scientific endowment and support for research.

Third and fourth phases still a dream

Fars: What is the status of the different phases of the lab?

The laboratory has been designed in phases. The first phase is fully operational, and the second is nearing completion. For this stage, we still need four or five key devices which we haven’t yet acquired. Once complete, about 90 percent of our operational capacity will be realised.

As for the third and fourth phases, for now, they remain dreams. But dreams are where motivation stays alive. If we can secure the necessary funding, those stages too will be implemented.

Fars: Any final remarks?

People should know that building the future begins with research. I always say that the first time I visited Ms Iran Gholami to present the lab proposal, she responded with hesitation. But once she saw how things progressed, she stepped forward enthusiastically, supporting us even without request.

I hope the media will help amplify our voice. Raising awareness, building trust, and fostering a culture of scientific engagement are key to advancing science in this country. Iran holds great potential. We simply need the right tools and proper attention.

For more information, please see the original Fars News article Founding of a philanthropic laboratory and the website of the AmirAalam Ghazanfaryan Electronic Materials Laboratory.

Mon, 09 Jun 2025

Developed by the IASBS Computer Centre

IP Address:[216.73.216.120] Browser: Mozilla/5.0 AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko; compatible; ClaudeBot/1.0; +claudebot@anthropic.com)